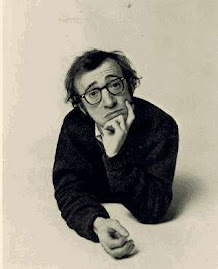

The marriage of film and self-destructive romance has been ironically faithful to one another. As long as film, literature, and humanity have existed, romance and all its struggles and inefficiencies have dwelt among us as well. The rebirth and redemption that love offers, as well as the monumental deficiency in an individual that unrequited or lost love can create is equally stirring in films. Romance and relationships are ingrained in life and experiences, thus this reality becomes an unrelenting force and theme within literature, art and cinema. Yet in the films of Woody Allen an especially concentrated view is on the erosion of love when a narcissist is involved. In Woody’s Allen’s films, although approached in comedic and classic fashion, to relate experiences of finding and losing love, vignettes and ideologies about self-destructive romance and narcissism is structured. Allen weaves a statement, through introspection into the relationships of the characters, that narcissism is the culprit behind self-destructive romance, but how through feeling the brunt of rejection the narcissist becomes somewhat redeemed and improved, and ultimately bears mental and virtuous growth as a human being.

Throughout Allen’s film Manhattan (1979) the ego-centrism of Isaac culminates an intriguing portrait of events, as he first falls in love and has a relationship with Tracy, knowing he’s holding her mentally captive as she is seventeen and vulnerable, then very easily shifts his affections to a woman of his own seemingly identical neurotic inclinations and cultural hauteur, who also happens to be his best friend’s mistress. Isaac’s ability to shift his decisions without a moral or ethical filter, although he does have a temporary but insincere regret about his actions, paints him as a narcissist who views his involvement with others through the lens of how they affect him. You can sense the inevitable disaster ahead as he breaks off his romance with Tracie, advances romantically with Mary the superior intellectual, and a mess of Manhattan sky-scraper proportions is set. Isaac’s waffling with these two women states to the viewer that his intensely remote consideration of others is straining his relationships with possible mates, as well as his friends. Yet the statement that is conducted through the outcome of Manhattan is that in the narcissist’s enlightening recognition of something or someone they should’ve treasured which they lost in light of their self-seeking mindset, the pain of that loss shocks them enough to bring them a step closer to reality and understanding their injury to others and themselves. Isaac’s surrender of Tracy to her own dreams and pursuits reveals that he is making a choice to hinder his own vanity and is furthermore slowly dwindling in his self-destructive habits that will hopefully lead to him having firm faith in people and in her instead of relying on his capricious whims and wants.

Significant dedication in literature has been to amorous characters that are chronically self-absorbed and seriously inadequate. For instance, the dashing, handsome, yet unsure Amory Blaine is a prime example of this breed of individual very similar to Allen’s characters. A superior education and systematic manipulation of the social systems in which he played, elected and savvy taste in cultural knowledge stated him as the darling of the 1920s in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel This Side of Paradise. Only sure of how others fit around and below him in social categories and mental perception and brilliance, Amory was the super-narcissist, who readers can imagine skirmished for a glance at his own reflection every opportune moment he could make. Amory’s experiences led him to many individuals he came to admire, but he still could not surrender his pathogen-like narcissism in his relation to them as he severely judged all those around him with himself as the standard and neophyte to aspire to. The last half and finally the denouement of the novel portrays Amory as recognizing and regretting his lost love, Rosalind, who truly loving Amory, unfortunately could not bind herself to what came with him: his social status and his wallet, which was inadequate compared to what she wanted to possess. Being disillusioned by the disappearance of intriguing acquaintances, the death of faithful friends and the dismissal of lovers, Amory’s narcissistic nature became suffocated as his utter loss and loneliness crept in and stole away his high opinion of himself. His last words bear in mind the embrace of himself in light of the results of how he previously lived, whereas throughout the novel Amory is not attentive to his uncertain and wavering dispositions on the world. “I know myself, but that is all” is not a condemning statement, but one of renewal where Amory acknowledges his narcissism and the miscarriages of his dreams that have stemmed from it, leading him forward into a refreshed perspective of his position in the world and growth as a human being despite his setbacks.

A majority of the narcissism found in Allen’s characters is rooted in a determined commitment to discover and maintain love and companionship and to triumph in the conquest of another. Yet the contrary results of the ego-maniac is that they are plagued by the effects of their stifling impulses and convictions and reap from them only detrimental woes in their worlds of love that Allen’s universe seems to revolve around. The characters’ quests for romantic happiness take awry turns and they find themselves with fizzled, disappointing results with the women they love, but why? Allen’s point in his films is that the shock of rejection and abandonment is necessary and essential to scoop the narcissist from their solitary philosophy and drop them into reality of their failures. A suitable example can be found in Woody Allen’s neurotic but likeable character Alvy Singer, in his modern romance Annie Hall (1977). Alvy educates, supports and stimulates Annie in Pygmalion-style but inevitably self-inflicts the relationship with his aggressive opinions that cannot be attested, and in Alvy’s eyes, cannot be illogical or unreasonable. Though their romance withers and Alvy underestimates the void her loss will have on him, the distance of Annie and debt of her presence actually improve him in the long run. When later reunited as friends, Alvy states: “I realized what a terrific person she was and- and how much fun it was just knowing her…” His “island” persona, identified by philosophizing himself into isolation from others, is wearing away and he begins to acknowledge and cherish the differences and company of others. Like the self-obsessed Scarlett O Hara’s last words in Gone With the Wind, when rejected by both Ashley and Rhett, “Tomorrow’s another day,” Alvy’s final, resting outlook is similarly one of growth and reflects a sense of hope and personal redemption from the cancerous consequences of his narcissism.

Allan Felix, an addition to the list of disastrously insecure characters in the films of Woody Allen, blazes the trail for understanding the other side of narcissism: that strain of the trait that fleshes out when one has lost something exceedingly valuable. In Allen’s film Play It Again, Sam, Allan is a man devastated from the divorce from his wife, and becomes consumed by his own anxieties, shortcomings with an elevated sense of self-consciousness. Combined, this is not a favorable mixture to a man considering dating again, and the unfortunate, though laughable results of his dating experience leads him to an admiration and infatuation of the one helping him along in the dating world: his best friend’s wife who looks to Allen as a sort of lost cause who she can aid. As he perhaps unconsciously manipulates her vulnerable position, as her husband’s business and work keeps him preoccupied, through companionship and investment in her he inevitably becomes involved with her without regard for his best friend’s feelings and her awkward circumstance, now loving two men at once. Allan’s removal from his mind of the consequences of his actions to the people involved (Dick and Linda) and his excessive concerned of his ability to woo Linda while still married identifies him as a slightly desperate narcissist on whom the viewer can have pity. As the relationship between Linda and Allan escalates and suspicion of an affair on Linda’s part is in the mind of Dick, Allan fizzles in the process of the stress his actions have brought him to. Linda’s earlier state of confusion and fickleness about what man she should be with is finally resolved as her husband is the victor in the end. She ultimately is given the power to do so through Allan’s sacrifice of what he truly wants. It is here that his ego-centric tendency is crushed as a true loss is felt, not only because he greatly appreciated and loved Linda but also because he is resigning a part of himself that governed him for a long period.

Specifically, Allan is parting from the cumbersome narcissist that wouldn’t have done “the right thing for a pal”. Bogart observes to Allan, “When you weren’t being phony, you got a good dame to fall for you.” Allan’s renunciation of the only relationship that flourished when he was simply being himself and not attempting to impress women makes his surrender of his attachment to Linda that much harder. Finally, when convinced he and Linda will confess to Dick their previous devotion to one another, Allan has compassion and not self-pitying thoughts about the quandary as he surrenders Linda and aids her in concealing their secret so as to protect Dick from knowledge of their affair and to protect the integrity of his friends’ trust to one another. Allan’s ravaging journey through dating, denial and detachment forces him to be enlightened about the “other things in life besides dames,” which he learns is sacrifice, honor and selflessness. His loss gives him the energy and encouragement to proceed into searching for love again without the inner-narcissist intruding; knowing that he once loved and was able to be loved greatly without selfish intentions.

The connection between narcissism and renewal cannot be denied; the reality and acceptance of the failures that hinder an individual from what they truly value eventually become processed as a lesson not only in pain and sacrifice but ultimately a departure from living as an egotist. Through the rejection of a beloved as a consequence of narcissistic behavior, the individual is launched into a world now surrounded by others and their best interests, not the narcissist’s personal importance. Their self-destructive ways they now see as a barrier between themselves and the world and in return their redemption as human beings is nurtured through the initial bitter taste of their love being forfeited.

Works Cited

Allen, Woody. Annie Hall. Rollins-Joffe Productions, 1977.

Allen, Woody. Manhattan. Jack Rollins & Charles H. Joffe Productions, 1979.

Fleming, Victor. Gone With the Wind. Margaret Mitchell. Selznick International

Pictures, 1939.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. This Side of Paradise. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920.

Ross, Herbert. Play It Again, Sam. Paramount Pictures, 1972.